When Voice AI Loses Track of Reality

Interruptions, Context Drift, and Lessons from Building Real Voice AI Systems

Modern voice AI systems feel conversational, but internally they rely on fragile assumptions about timing, audio delivery, and shared context. When those assumptions break, the failures are subtle, cumulative, and difficult to diagnose.

Voice AI systems usually do not fail in dramatic or obvious ways. Instead, they fail quietly. They do not crash. They do not obviously hallucinate. They simply continue the conversation as if something was said and understood, even when the user never actually heard it.

The result is a voicebot that repeats itself, answers questions the user did not hear, or assumes agreement where none was given. Over time, this slowly erodes user trust.

Context

The observations in this article are drawn from building and operating production-grade voice AI systems at CARS24, India’s largest automotive transaction platform. At CARS24, voicebots are used across high-stakes customer journeys such as vehicle discovery, sales follow-ups, appointment coordination, and post-transaction communication. These interactions are conversational, time-sensitive, and often interrupted, making correctness under real-world conditions a non-negotiable requirement.

While the examples here are generalized and anonymized, the failure modes and architectural lessons are directly informed by real systems that were deployed, observed at scale, and iteratively improved in production.

Two Common Architectures for Voice AI

To understand why interruptions are so hard, we first need to distinguish between two very different ways of building voice AI systems.

There are two main architectural approaches to Voice AI. The choice between them strongly affects how interruptions behave.

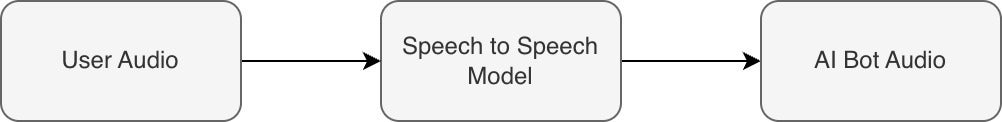

1. End-to-End Speech-to-Speech Models

Speech-to-speech systems take audio as input and produce audio as output.

Key properties

1. Very low latency

2. Natural-sounding turn-taking

3. Simple high-level pipeline

Limitations

1. Typically cost 2–3x more than text-based LLM systems

2. Much smaller context windows (often ~10x less than text LLMs)

3. Limited visibility into intermediate reasoning

4. Difficult to debug, inspect, or steer

This system works best for short, simple, and reactive interactions, but it struggles with longer conversations that require memory or reasoning.

Common use cases

1. EMI reminders and payment nudges

2. Booking rescheduling or simple status updates

3. Short transactional notifications

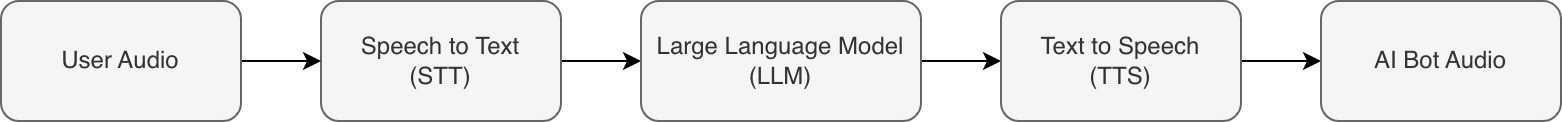

2. Modular STT → LLM → TTS Systemations (delivery alerts, appointment confirmations)

Most production voicebots today use a modular pipeline that separates speech recognition, reasoning, and speech synthesis.

Advantages

1. Large and inspectable conversation history

2. Explicit control over prompts and context

3. Strong performance on multi-turn tasks

4. Lower and more predictable cost

5. Flexibility to swap individual components

Trade-offs

1. Higher end-to-end latency

2. More components that can fail

3. Interruption handling becomes complex

Deep diving into the problem

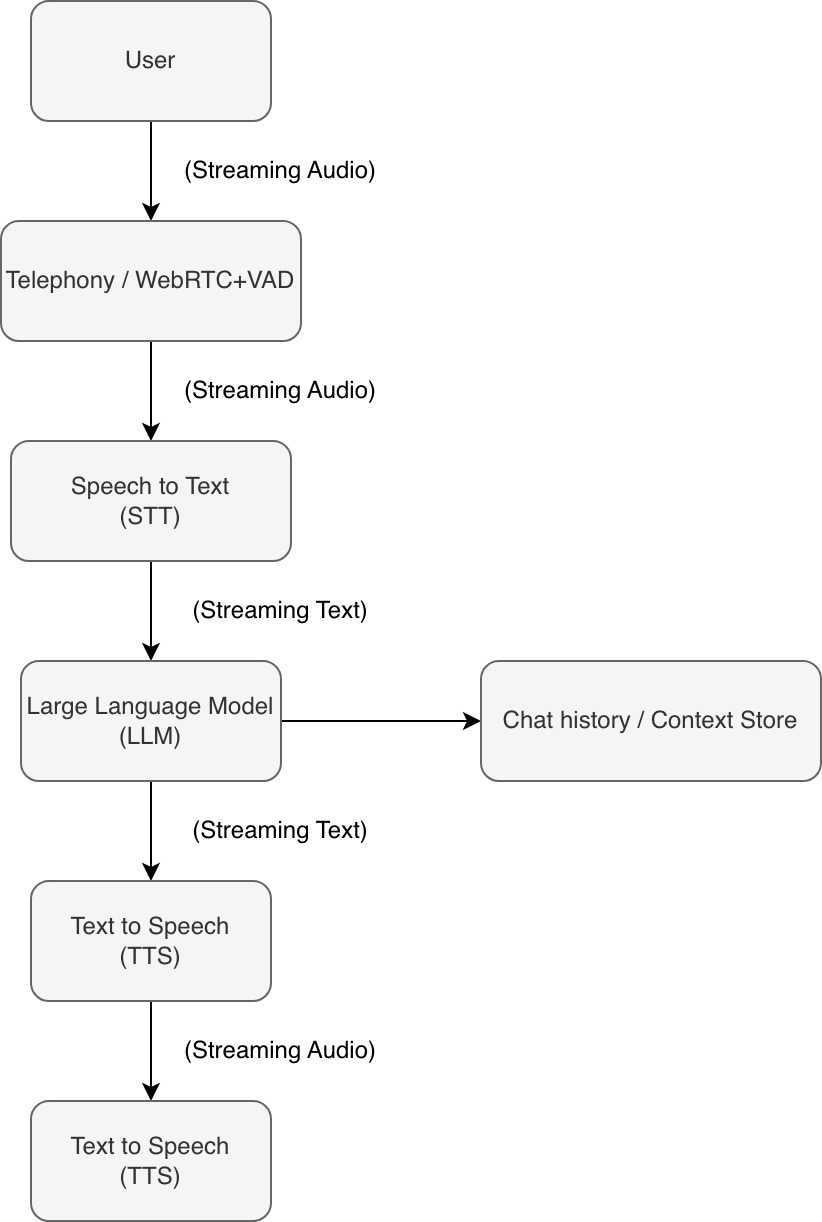

How Context Is Stored in Practice

A crucial implementation detail in modular voice systems is how conversation history is recorded.

When the LLM generates a response, that text is immediately:

- Saved to the database

- Added to conversation history

- Used as context for the next turn

This design assumes that whatever the LLM generated was fully heard by the user.

Interruptions break that assumption.

Why Interruptions Corrupt Context

Users interrupt voicebots all the time:

· To correct something

· To ask for clarification

· Because human conversations overlap naturally

When an interruption happens:

· Audio playback stops

· But the LLM response is already fully generated and stored

The system believes the full message was delivered. The user only heard part of it. This difference compounds over multiple turns, causing the system’s internal context to drift further away from the user’s actual experience.

Why Stopping Audio Is Not Enough

Modular voice systems are asynchronous and buffered.

· LLMs generate text much faster than audio can be played

· TTS systems buffer audio for quality and efficiency

· Network and telephony add additional delay

· Voice Activity Detection triggers after sound is detected

By the time an interruption is detected, the text has usually already been committed as history.

So the real problem is not audio playback.

It is knowing what the user actually heard.

A Concrete Failure Mode: When “Yes?” Means “I Didn’t Hear You”

To make this failure mode tangible, consider a short exchange between a sales voicebot similar to those used at CARS24 for vehicle discovery and lead qualification, and a prospective customer.

The bot is mid-pitch, describing a feature set. The user interrupts, not to agree, but because they missed part of the sentence.

Bot: This model comes with adaptive cruise control, lane-centering assistance, and a complimentary three-year

User: Yes?

Bot: Great! I’ll go ahead and book a test drive for you this weekend.

From the human’s perspective, “Yes?” is a request for repetition: What did you just say?

From the system’s perspective, the interpretation is very different.

Internally, the LLM has already generated and persisted the full utterance: “This model comes with adaptive cruise control, lane-centering assistance, and a complimentary three-year maintenance package.”

When audio playback is interrupted, only a prefix reaches the user. However, the chat history reflects the entire sentence. When the user says “Yes?”, the system maps it onto the stored context and interprets it as affirmation rather than confusion. The bot is not being reckless. It is being internally consistent, just with the wrong reality. This is the essence of the problem:

A minimal interruption produces a semantic inversion. A clarification request is misread as consent, not because the language model failed, but because the system’s notion of shared context is already corrupted.

The Remedy

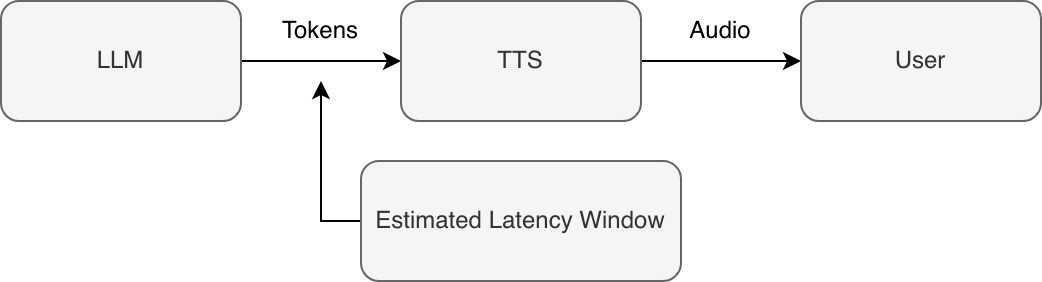

Attempt I: Streaming with Latency-Aware Truncation

In practice, the system was already fully streaming. LLM tokens were generated incrementally, passed to TTS as soon as possible, and rendered to the user with minimal intentional buffering.

The remaining problem was not whether the pipeline streamed, but how far ahead the LLM was allowed to get relative to audible playback.

Strategy

· Stream LLM tokens continuously

· Feed tokens into TTS immediately

· Maintain an estimate of audio playback progress

· Truncate the committed LLM output to account for end-to-end latency when an interruption is detected.

Example: Truncating the last 2–3 words of the LLM output before storing it into the context, every time an interruption is detected.

Outcome

While this reduced worst-case divergence, it remained fundamentally approximate. Latency varied across TTS buffering, network jitter, and telephony playback. As a result, the truncation boundary was necessarily heuristic.

Under realistic load, the system was still routinely off by several words, occasionally more during spikes. The approach bounded the error but could not eliminate it.

Crucially, this meant the system was still inferring what the user had heard, rather than knowing it. The epistemic problem remained.

Attempt II: Loopback Transcription

To remove guessing, the system shifted its focus from prediction to observability.

Instead of trying to infer what the user might have heard, it attempted to measure what was actually spoken out loud.

This attempt was motivated by a simple insight: if the system could listen to itself in real time, then the stored context would necessarily match the user’s auditory experience.

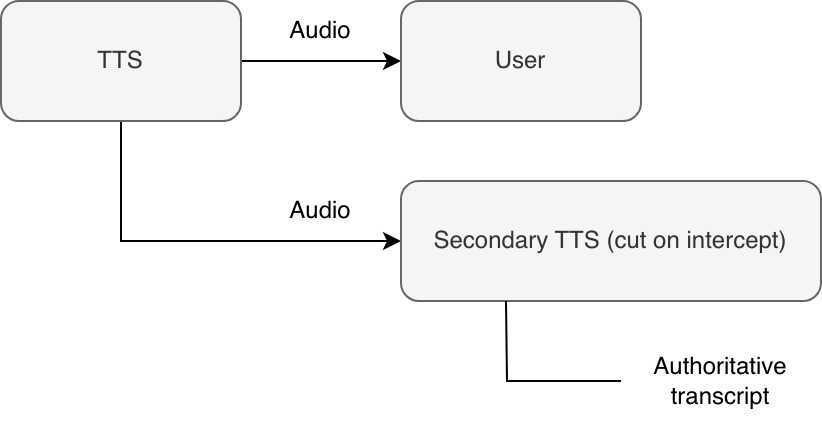

Approach

· Send TTS audio to the user as usual

· Mirror the same audio stream into a secondary STT system

· Treat the secondary STT output as the source of truth for what was spoken

· Immediately stop transcription when an interruption is detected

In effect, the voicebot became its own listener. Whatever the secondary STT successfully transcribed before the interruption was what got committed to memory.

Why this worked

· Eliminated timing guesses entirely

· Guaranteed alignment between spoken audio and stored text

· Correctly handled mid-sentence interruptions

Why it didn’t ship

Despite its conceptual cleanliness, this approach came with serious trade-offs:

· Cost: Running an additional real-time STT pipeline roughly doubled inference cost

· Latency: Transcription lag introduced delays in committing context

· Complexity: Debugging two tightly coupled real-time audio paths was brittle

· Failure modes: STT errors now directly corrupted bot memory

Loopback transcription proved that perfect alignment was possible but at a cost profile that was hard to justify at scale.

Attempt III: Timestamped TTS (Shipped Solution)

The final solution reframed the problem entirely.

Instead of listening to the audio after it was produced, the system embedded truth directly into the audio generation process itself. Time, not transcription, became the source of authority. This attempt is the core contribution of the system and the primary takeaway of this article.

Key idea

If the system knows exactly when each word is spoken, then it never needs to guess, estimate, or re-transcribe. Interruption handling becomes a deterministic bookkeeping problem.

Approach

· TTS emits audio with word-level timestamps

· Each token is aligned to precise playback intervals

· Actual playback time is tracked continuously

· When an interruption occurs, only words whose timestamps fall before the cutoff are committed to context

“Hello” [0–280 ms]

“there” [280–620 ms]

“today” [620–980 ms]

Interrupt at 700 ms → commit: “Hello there”

Why this matters

This architecture guarantees a strict invariant: The system’s memory is always a prefix of what the user actually heard.

No more, and no less.

Advantages

· Zero re-transcription cost

· Deterministic behavior under interruption

· No dependence on network variability

· Minimal added latency

· Clean separation of concerns between LLM, TTS, and playback

Engineering insight

The key realization was not about improving interruption detection or changing language model behavior. It was about where truth is allowed to enter the system. In a modular voice pipeline, the LLM is an upstream producer of intent, not an authority on shared reality. It can generate faster than audio can be played, and it has no direct visibility into what was actually heard. Treating its output as ground truth creates an implicit and fragile assumption: that generation implies delivery. The system became reliable only after this assumption was removed.

By deferring commitment of conversational state until the moment text is bound to audible playback, using deterministic, timestamped alignment, the system enforced a strict invariant: only what was actually spoken can become part of memory.

This reframed interruption handling from a conversational or UX concern into a systems concern: deciding which component is allowed to assert truth, and under what conditions. Once that boundary was explicit, correctness under interruption followed naturally.

Why this shipped

Timestamped TTS achieved the best balance across all constraints:

· Correctness under interruption

· Predictable cost

· Operational simplicity

· Scalability to production traffic

It is the only approach that fully eliminates context drift without introducing new sources of uncertainty, and it remains the architecture used in production today.

At CARS24, this approach proved robust across diverse user devices, variable network conditions, and large volumes of real customer conversations, all without requiring changes to model behavior or conversation design.

Why This Matters in Real Automotive Workflows

Automotive conversations are rarely clean, single-turn exchanges. At CARS24, customers interact with voicebots to negotiate, clarify vehicle details, change availability, or switch topics entirely.

In these contexts, a voice system making an incorrect assumption, even once, can prematurely confirm an action, misinterpret intent, or damage trust in a high-value transaction.

The interruption-handling issues described in this article were not theoretical edge cases. They emerged precisely because the system was exposed to real customer behavior at scale. Solving them required treating conversational truth as a first-class systems concern, not a UX afterthought.

Key Engineering and Product Lessons

- Many voice AI failures are systems problems, not model problems

- The language model may be correct in isolation, yet still produce wrong outcomes when the surrounding system misrepresents shared context.

- Latency affects correctness, not just performance

- In streaming systems, time determines meaning. A few hundred milliseconds can flip intent, consent, or commitment.

- Context errors accumulate silently

- Small mismatches between what was heard and what was stored compound over turns, eventually producing behavior that feels irrational to users.

- Users forgive mistakes, but not false assumptions. People tolerate repetition and clarification. What breaks trust is when a system confidently acts on something the user never agreed to.

Closing Thoughts

Interruption handling in voice systems is often treated as an edge case. In reality, it sits at the core of conversational trust. The lesson from this system is not that timestamped TTS is the only solution , but that shared reality must be enforced explicitly. Whenever a system assumes mutual understanding without verifying it, subtle bugs turn into product failures.

No amount of model quality compensates for a system that misunderstands what it has actually communicated. The systems and approaches described here were shaped by hands-on experience building AI voicebots at CARS24, where conversational correctness directly impacts customer trust and business outcomes. As voice interfaces continue to play a larger role in real-world commerce, the lessons from these systems, particularly around interruptions, timing, and shared context, are increasingly relevant beyond any single company or product.

Loved this article?

Hit the like button

Share this article

Spread the knowledge

More from the world of Cars24

Building Resilient Node.js BFFs at Scale: Hard-Earned Lessons from Production

The difference between a BFF that handles 100rps and one that handles 10,000rps isn’t some magical framework.

From Feedback to Visible Change: A Gentle Rhythm for Team Observability

Leaders spend less time firefighting and more time enabling, because patterns in the trend point to structural fixes.

Supercharge Your Gupshup Campaigns with Cloudflare workers

Deep linking third-party URL shortening services via Cloudflare bypasses limitations like restricted file hosting by leveraging Cloudflare Workers to dynamically serve necessary files.